🌊 The maritime security architecture in the Western Indian Ocean has developed new pace since the emergence of Houthi attacks on commercial shipping and the resurgence of Somali piracy activities last year. This week I attended the naval coordination SHADE conference in Bahrain, where these critical developments took center stage.

SHADE in full work mode

🤝 SHADE serves as a vital interface between the complex network of multinational and independent naval forces and the shipping industry. The EU’s Operation Atalanta and the US led Combined Maritime Forces (CMF) co-host this forum which has evolved from its original focus on piracy to become a comprehensive annual dialogue.

📊 It has now upscaled activities and launched three working groups dedicated to intelligence, information sharing, and operations. The key objectives are to give better advice to shipping, improve flow of information, and develop better emergency response coordination, including oil spill prevention.

SHADE is working towards what it calls a ‘Single Information Environment’. This could streamline information flow across the six information sharing centers focused on the region. A corner piece is a center started in 2024 – the Joint Maritime Information Center (JMIC) – which supports the CMF.

The European Union’s continued commitment

🇪🇺 The European Union continues to demonstrate strong commitment to regional maritime security. Operation Atalanta’s mandate has been renewed for two years, and its sister operation, Aspides, is expected to be extended until 2026.

There are expectations that the two EU operations will be merged soon. Anticipating this merger, the EU has rebranded its information sharing center. It now runs under the name of Maritime Security Center Indian Ocean (MSCIO), serves both operations and has a brand new website.

CMF and regional contributions

🌏 CMF, which is organized in different task forces and remains focused on nonstate threats on the high seas, has expanded its membership significantly, turning it into an important umbrella organization under US leadership.

🌏 Regional leadership in maritime security has also grown impressively: India has emerged as a pivotal maritime security provider; the Indian Ocean Commission’s two centers have become key operational pillars, coordinating responses among Eastern African states; and the Djibouti Code of Conduct (DCOC) has evolved into a more effective capacity building coordination mechanism.

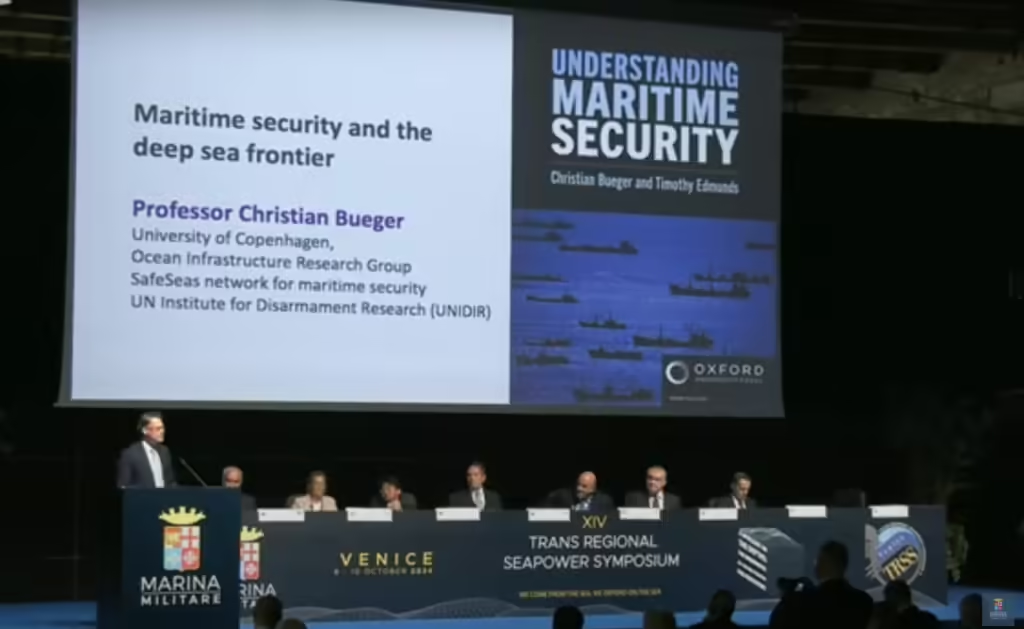

⚓ As I highlighted in my presentation: Though this new momentum is encouraging, maritime security threats persist, and shipping attacks continue to pose challenges. Success requires sustained engagement and investment with a long-term perspective.