The seabed is rapidly becoming a new space of concern in security politics. In Europe, largely triggered by the 2022 sabotage of he Nord Stream pipelines, but also investments by Russia in subsea capabilities, NATO countries are reevaluating their dependency on subsea infrastructures such as pipelines and data and electricity cables.

As part of their EU presidency, the Spanish Navy hosted a Forum focused on the issue on November, 16th at naval headquarters in Madrid. Titled the “Seabed, a new area of interest and dispute”, 150 participants, including high level representatives from all major European navies, discussed the importance of the seabed, and different responses.

The first panel focused on the strategic picture, deep seabed mining and subsea data cables. In the second panels, the navies of Spain, Italy and France provided an overview of the defense and coordination projects they are currently developing. The French representative showed how the navy is implementing its dedicated seabed strategy, while Italy discussed how their response is structured by technological innovation, maritime stakeholder communities, a legal review and the creation of a new coordination center.

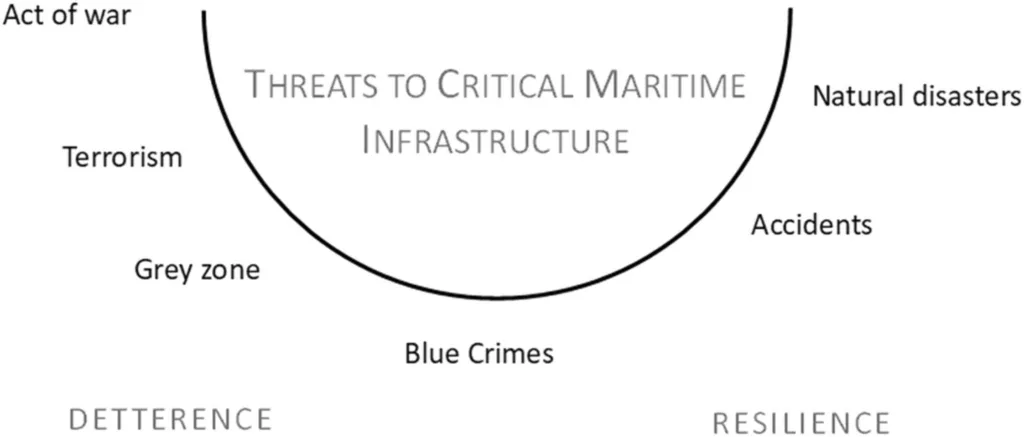

In my contribution to panel 1, I firstly argued for the need to think maritime security in dimensional terms. I then demonstrated how substantively our dependency on the seabed has been accelerating in the past two decades, a trend that will continue with the green energy transition is unfolding. Two make that point, I provided a review of how the seabed has been used throughout history. I then investigated the hypothetical landscape of threats based on our recent article on the issue. I ended in an evaluation of current European responses and its challenges.

The main responses are led by NATO and the EU. NATO has developed a coordination cell in its headquarters which organizes a stakeholder network described as ‘community of trust’. At NATO Maritime Command a center for critical infrastructure protection is being developed which will operate in a similar way as the NATO Shipping Center to enhance information sharing and coordination with industry.

The EU is currently evaluating the vulnerability of subsea infrastructures, and has recently launched its EU Maritime Security Strategy that entails significant plans for infrastructure protection. A key actor driving the agenda is the European Defense Agency.

More efforts will be needed, however, in improving maritime domain awareness and subsea awareness, reliable information sharing and standards for the self-protection by the industry.